Burn

Subject: Child Health Nursing

Overview

Burns

Burns are injuries to the skin or other body tissues brought on by too much heat. When the skin's or other tissues' cells are completely killed by heat, electrical discharge, friction, chemicals, or radiation, a burn has occurred. Due to their thinner skin, children under the age of five and adults over the age of 55 are more prone to deeper burns.

The degree of exposure (heat or radiation), the length of the exposure, and the cause of the burn all influence the tissue damage. Burns are the second most common accidental injury in children and a serious global public health issue. The majority of minor burns can be treated in primary care settings, but complex burns and all major burns necessitate a specialized, skilled multidisciplinary approach for a positive clinical outcome.

Types and Etiology of Burns

- Heat/Thermal burns:

The most frequent causes of thermal burns are steam, hot solid objects, hot liquids, and flames. The depth of the thermal injury is influenced by the skin's thickness, contact temperature, and length of time exposed to the external heat source. - Electrical burns:

occurs as a result of lightning, improper handling of wires, irons, and ovens. - Radiation burns:

The sunburn is the most prevalent radiation burn type. - Inhalation injury:

Inhaling heat smokes, chemical irritants, fumes, or vapour can result in burns injuries to the respiratory tract. - Friction:

The combination of mechanical tissue disruption and frictional heat generation can result in friction-related injury. - Chemical burns:

occurs as a result of ingesting or coming into physical contact with caustic substances, such as potent acids, alkalis, detergents, or solvents. The severity of the harm will depend on the length of exposure and the type of agents. While alkaline burns result in liquefaction necrosis, contact with acid induces coagulation necrosis of the tissue. Some chemicals can cause life-threatening systemic absorption, and local injury can affect the entire thickness of the skin and underlying tissues.

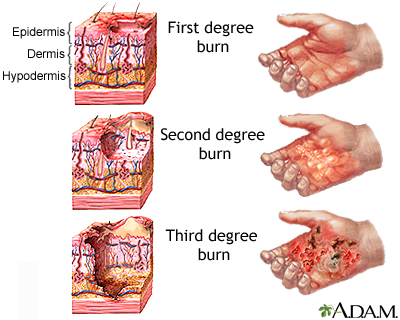

Classification of burns by depth of injury

1.Superficial (epidermal)

- involve only the skin's epidermal layer.

- Skin that is erythematous, dry, and without blisters

- Blanches under stress

- Due to irritation of the nerve ending, painful, and discomfort increases with touch

2.Partial-thickness

- The epidermis and a portion of the dermis are affected by burns.

- Formation of blisters (clear fluid-filled blisters)

- Red, weeping, and moist wound that is oozing clear fluid

- Blanches under stress

- Temperature, air, and touch hurtful

3. Deep Partial Thickness

- Burns penetrate further into the dermis.

- Blisters (easily unroofed) (easily unroofed)

- Wet, waxy, dry, and of varying colors (patchy cheesy white to red)

- Pressure-induced blanching might be sluggish.

- Only painful under pressure

4. Full -thickness

- Burns penetrate all dermal layers, obliterating them, and frequently harming the subcutaneous tissue beneath.

- Burns with a full thickness are typically anesthetized or hypo-anesthetized.

- Skin can appear in a variety of ways, including waxy white, leathery gray, and charred and black.

- Blisters and vesicles do not form.

- Skin does not blanch under pressure and is dry and inelastic. Hair follicles are simple to remove hairs from.

5.Deeper injury (ie, fourth degree)

- Deeper burns penetrate the skin into the soft tissues beneath, including the fascia, muscle, and/or bone.

- Burns are serious, potentially fatal injuries.

- Deeper harm

Clinical manifestation

Burn victims also experience other clinical manifestations in addition to the skin damage mentioned above, including:

Shock

Symptoms of shock often appear shortly after burns, and a child may exhibit them.

- High heart rate, low blood pressure, low temperature, pallor, cyanosis, and prostration.

- Having weak muscles and having trouble recognizing a familiar face.

Toxemia

1-2 days after burns, symptoms of toxemia, such as

- Fever and a fast heartbeat oedema and vomiting

- Decreased urine output and glycosuria

- May result in a coma or death

Upper respiratory tract injury

- Burns to the airways can result in swelling or inflammation of the upper trachea, vocal cords, and glottis. Upper airway obstruction symptoms like dyspnea, tachypnea, hoarseness, stridor, substernal and intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, restlessness, drooling, and cough are what distinguish it from other conditions.

Smoke inhalation

- Initial phase without any symptoms other than a slight bronchial obstruction. A child may experience the sudden onset of bronchiolitis, pulmonary edema, and severe airway obstruction within six to 48 hours.

Estimation of extent of burn injury

To direct therapy and choose the appropriate time to transfer a patient to a burn center, a thorough and precise evaluation of the burn size is crucial. The entire percentage of body surface area is used to measure and express the amount of burns (ie, TBSA). Using a Lund Browder chart, the Rule of Nines, or the palm method can help with this estimation. The Lund-Browder chart is the most precise technique of assessing TBSA burn in children. The palm approach might be more practical if the burn is uneven and/or spotty. The % TBSA burn assessment excludes superficial (first-degree) burns.

- Lund-Browder

The most precise method for calculating TBSA in both adults and children is the Lund-Browder chart. The Lund-Browder chart provides a more accurate estimate of the percentage TBSA because children's heads and lower extremities are proportionally larger and smaller.

- Palm method

The patient's palm's surface area can be used to estimate small or patchy burns. The patient's hand's palm, excluding the fingers, makes up about 0.5 percent of the body's total surface area; in children and adults, the entire palmar surface, including the fingers, makes up 1 percent.

Therapeutic Management

The initial care for burn wounds primarily entails removing clothing and other debris, cooling, straightforward cleaning, suitable skin dressing, pain management, and tetanus prophylaxis. Below is a detailed description of management.

- Cooling

Burn wounds can be cooled with room temperature or cool tap water to provide some pain relief and prevent tissue damage after removal of clothing, jewelry (such as rings, which restrict circulation and cause edema), and non-adherent debris from burns wounds. It is recommended to apply cool, calm, or running water until the pain subsides, but not for more than five minutes at a time to prevent macerating the wound. A different option is to cover the wound with wet gauze or towels, which can lessen pain without submerging the wound and can be left on for up to 30 minutes,prior to dressings being put Ice or iced water should not be applied directly because doing so can worsen pain and burn depth. One efficient method of cooling is to apply gauze that has been soaked in water or saline and cooled to about 12°C (55°F). When cooling burns that cover more than 10% of the total body surface area, patients, especially young children, should be closely watched for hypothermia. - Pain management (analgesia)

Paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen, are frequently used alone or in conjunction with opioids, such as morphine and oxycodone, to treat minor burn injuries. Prior to changing into new clothes and engaging in more physical activity, pain medication should first be given continuously around-the-clock. For several days following the injury, pain and swelling can be decreased by elevating burns to the lower and upper extremities above the level of the heart. A suitable method for reducing pain soon after the burn is sustained is to apply gauze soaked in cool water to the wound for up to 30 minutes. - Cleaning

When changing the dressing, burn wounds should be cleaned every day with only mild soap and water. Cleaning burn wounds with chlorhexidine wash (without alcohol) is also efficient. Avoid using skin disinfectants like povidone-iodine because they inhibit the - Debridement

Before putting on a dressing, sloughed or necrotic skin, including ruptured blisters, should be debrided. Skin remnants from necrotic blisters may lower the chance of infection and prevent topical antimicrobials from reaching the burn wound. - Blisters

With shallow or deep partial-thickness burns, blisters can form. Debriding should be done on ruptured blisters. Blisters that are still intact shouldn't be aspirated with a needle because doing so increases the chance of infection. Long-lasting blisters that don't heal after a few weeks suggest a possible deep, partial- or full-thickness burn underneath, necessitating a referral to a burn center or a surgeon with experience treating burns. - Antimicrobial therapy

Superficial burns (eg, sunburns) and superficial partial-thickness burns rarely prone to bacterial colonization; therefore do not require a topical antimicrobial agent. Application of moisturizing cream is enough for superficial burns. A topical antibiotic should only be applied to partial-thickness or full-thickness burns.Silver sulfadiazine (SSD) has been commonly used for prophylaxis against infection for more extensive partial-thickness burns; however, treatment with SSD may slow wound healing and increase the frequency of dressing changes, resulting in increased pain. Modern hydrocolloid and silver impregnated dressings may be superior to SSD. Tetanus immunization should be administered, particularly for any burns deeper than superficial thickness. - Dressings

Dressings are not required for minor burns. Even so, full-thickness and partial-thickness burns typically call for dressings. Smaller burns on the face or hands that don't involve fingers can frequently be treated without dressings by first gently washing them with a mild soap and then applying a topical medication. Dress burns that involve the fingers or toes properly to avoid adhesion and maceration. Burn debridement and dressing adjustments are painful processes, thus effective pain management is crucial. To achieve the best pain control, it is advised to administer painkillers at least 30 minutes before changing a dressing. - Basic dressing

A simple gauze dressing is sufficient for covering burns. It comprises of a first layer of nonadherent gauze placed over the burn, a second layer of soft dry gauze, and an outer layer of an elastic gauze roll. It is applied following the application of a topical antibiotic. A burn center may need to receive certain patients with mild burns for reevaluation and treatment. In such circumstances, only dry, nonstick gauze should be used to cover all burns. Moist gauze dressings worsen wound maceration, raise the risk of hypothermia, and deepen burns. In order to avoid hypothermia and avoid unneeded delays, patients who have had burns should be kept warm during the transfer to the burn center. - Dressing changes

Depending on the type of dressing being used, the recommended intervals for changing them varies from twice daily to weekly. On the other hand, non-adherent gauze dressings and topical antibiotic ointment should be changed once daily. When dressings become soggy from excessive exudate or other fluids, it seems best to change them. A moisturizing cream (such as Vaseline Intensive Care, Nivea, coconut oil, or cocoa butter) should be applied to the burn wound once epithelialization has taken place until natural lubricating mechanisms resume.

- Pruritus

During the healing process, itching is a common issue. Although topical medications and moisturizing lotions can also be used, systemic antihistamines (such as oral diphenhydramine) are usually the first line of treatment. - Oral burns

Ingestion of extremely hot liquids or solids, inhalation of hot vapors or liquids, or holding flammable or corrosive objects in the mouth can all result in oral burns. Cooling with water should be used to treat oral burn, and signs of airway compromise should be watched for.Topical antibiotic ointment and sporadic Vaseline application to prevent the lips from drying out are two treatments for mild burns along the lips and oral commissure (corner of the mouth). Saline rinses and basic oral hygiene are usually all that are needed to treat minor oral mucosal burns. Mouthwashes with alcohol in them should be avoided because they can irritate wounds and make them more painful. Young children with oral scald burns should receive special attention because their airway structures are more delicate, more susceptible to obstruction, and have milder degrees of swelling and inflammation. Consultation with a burn specialist should be sought out if there is any concern regarding an airway compromise or the severity of the injury. - Fluid Resuscitation

Oral rehydration therapy and additional maintenance IV fluids may be used to treat children with burns that are 15% TBSA or less. Ringer solution with added lactose is typically used for intravenous fluid replacement. For burns with more than 15% TBSA, the consensus formula is frequently used to calculate the amount of fluid required for resuscitation.

Consensus formula

- Body weight (kg) * TBSA% burned, 2-4 ml Ringer lactate (RL) or Normal Saline (NS).

- During the first eight hours, you receive half of your daily recommended fluid intake. The balance is distributed over the following 16 hours.

Management of Major Burns

Maintaining ABC is required for managing severe burns.

- Give 100% oxygen if it is recommended owing to respiratory issues brought on by noxious agent inhalation or respiratory burn.

- Optimizing nutritional assistance, managing long-term wound complications (such contractures), and providing psychosocial support to parents and children to lessen stress and worry are all part of the ongoing management of a badly burned patient.

- Escharotomy of the chest is performed to relieve chest constriction and promote ventilation when a full-thickness burn completely surrounds the chest, restricting chest wall excursion and making it difficult for the youngster to breathe.

- Keep an eye on blood gas readings, particularly carbon monoxide levels.

- An endotracheal tube is inserted in order to maintain the airway if the child displays altered sensorium, air hunger, or other signs of respiratory distress.

Prevention

- Encourage the parents to check the temperature of the bath water before adding any water or placing the child in the tub. In the bathtub, keep an eye on young children at all times to prevent them from turning on the hot water tap or pouring hot water.

- Children should not be given hot meals or beverages since they may be hotter than they appear to be. Keep a glass of boiling liquid out of the reach of children.

- Avoid using tablecloths that hang over the edge of the table because young children and curious toddlers might pull them back to see what's on the table.

- Children who can comprehend the dangers of fire should be taught to "stop, drop, and roll" if their clothing catches fire.

- Never leave young children unattended in the kitchen or among fireworks without constant adult supervision; instead, carry or hold the young child on your lap when working in the kitchen or around fireworks.

- Keep electrical cords tucked away and the electrical wall socket secured with safety plugs. Do not let electrical cords hang over a counter or table; keep electric appliances toward the backs of counters.

- Encourage parents to keep cigarettes, incense, hot pans, hot foods, and burning candles out of children's reach. Keep chemicals, lighters, and matches in locked cabinets and out of children's reach.

Things to remember

© 2021 Saralmind. All Rights Reserved.

Login with google

Login with google